Hood River Barren Lands

Prose poem by Tricia Daum

Photos by Daphnée Rouleau

January 2026

A de Havilland Twin Otter and Cessna Caravan carry nine companions and me from Great Slave Lake to north of tree line in Nunavut with food, canoes, and camp supplies for a twelve-day river journey. My torso is chilled while a heating vent uncomfortably blasts hot air onto my booted feet in the non-pressurized cabin. Below the plane, on the ground, snow blown by winter storms and subjected to cold temperatures, caught in esker leeward slopes remains this late June day. This is Canada’s Arctic, 67 degrees north.

After two hours of travel, the meandering turquoise Hood River appears below. Our bush pilot slows the float plane while the engines roar; he circles a dozen times. He wants enough river depth and parallel banks to serve as a runway for the pontoons. The plane descends lower each circle to finally splash down below Kingaumiut Falls. He backs pontoon rudders to a gentle riverbank, hammers a steel rod into the sand, attaches a painter to park the airplane. We canoeists step ashore to unload equipment and set up camp. After the two planes noisily depart, we are left alone in the Hood River’s serenity.

Across the Hood, three muskoxen graze on a verdant river bench. I stern one of five canoes upriver, eddy hopping, and ferry to the rocky shore below the three massive animals. After beaching canoes and securing them, we arctic visitors creep and crawl, binoculars in hand, cameras at the ready. We ascend dwarf birch, moss and lichen to view the horned, furry grazers.

Aware of us interlopers, the largest animal swings its heavy head, slashing at vegetation, advising us of his strength and prowess. Don’t mess with us. Its blonde shoulder hump rises above the large, snouted head. Dark brown fur drapes like a curtain to delicate ankles that seem unlikely to support the muskox. And yet when the animals turn eastward towards a higher river bench, they run with grace, speed, power.

Next day after breakfast, keen-sighted Zack points out two caribou south of camp. The larger one turns to observe us strangers. We near-sighted people, not needing to forage or feel threatened, use strong binoculars to better observe the pair. The two creatures, more curious than alarmed, carry on with their plan and amble west in their search for lichen.

Before leaving camp on our first paddling day, Colin, one of our three Black Feather adventure company guides, points to cross bars printed on the Hood River map. Rapids will be spicey today. We may at times scout the river from shore or read the river as we run the current.

Paddling a loaded canoe all day in Canada’s Barren Lands is a treasure, a privilege. As the river takes us east, I swivel my head in all directions to marvel at the landscape. Though barren of trees, the land is lush with grasses, pink and purple flowering shrubs, and yellow lichen. Creeks enter and enlarge the Hood from right and left. Birds squawk – rapids roar. Wind at my back. I rotate my shoulders, uncoil, and draw the paddle blade through the water. One stroke at a time cumulates and takes us further downstream. The only sounds – those of nature and moving water.

Last winter’s snow crouches in ravines and lingers on leeward slopes creating shapes that engage my imagination. Dove with wings spread. Fish with fluked tail. Butterfly. On shore — cotton grass seed heads blow even in a slight breeze like patriotic flags. Black basalt cliffs from volcanism of eons past stand as jagged cliffs only to be plucked, polished, and rounded into river cobbles.

White guano cascades from a vertical rock wall on river left, pointing upwards to a ledge that holds willow roots and sticks crafted by a gyrfalcon pair as a multi-season nest. My binocs, not my naked eye, reveal squirming heads of brown chicks. One of the brooding parents circles above calling out, worried. It perches across the river to watch over its young. My friends and I quickly retreat to the canoes and continue downstream.

In this year, my ninth of river paddling, I approach rapids calmly with gentle forward strikes as Colleen, one of the guides, steers the canoe with efficient lines, threading the needle between whirlpools and rock dangers. I listen to implement the strokes Colleen calls out: pry, draw, cross, power, pause. I obey without question.

Colin, because he has paddled the Hood several times, knows where to pull over on river right to find wolf dens: caves excavated by wolves in river bench soil and partially hidden with willow shrubs. Once on shore I crouch with my camera to take a close-up photo: a large wolf print and a cub’s faint track on the sandy beach. We all scan the landscape in all directions with binoculars—searching for wolves. None, not today. We stumble upon several ground squirrel dens that were recently demolished by a grizzly. We find a centuries-old tent ring and caribou bone fragments. Wolf scat with a gleaming caribou tooth.

Paddling downstream and above a rocky shoreline Colin notices movement —a fox. We paddle quietly and disembark on river right. In our scramble to reach a viewpoint and observe the fox we try, but fail, to travel without a sound. A herd of elephants would be quieter. I crawl to the rock rise, lie still and put the binoculars to my eyes. Magnificent reward.

A dark brown arctic fox with spindly legs, fluffy tail, perky ears, generous snout and beady black eyes stares at us humans. We are mutually curious. If that is he, then the dainty smaller she trots atop the den home. Her fur is red-tinged and blonde, the slender legs brown. Perhaps a blend with the southern red fox.

The third scenic gift—a frisky cub born this spring. All poufy and light brown. Black pin dot eyes and nose. It could care less that we spies focus our binoculars on it. The cub is more relaxed than its protective parents who understand threats. The cub sits on its haunches, scratches its chest, shakes its little head without concern. Proudly prances and lifts its nose to sniff its mother.

The male curls in a tight ball below mother and cub. His generous tail curls to encompass his entire body. He is prone but alert. Ready to do what might be needed to protect the family.

In morning’s camp below Wright waterfall, a Lapland larkspur suddenly flaps its wings, screeching and ascending from a local willow shrub. She attempts to direct the camper people away from her nest. Three tiny pinkish beaks punctuate grey bodies curled into one ball. Chicks, recently born. We make a wide berth around the nest. Pack up camp. Load canoes. Paddle downstream.

A muskoxen herd quietly grazes on a generous tundra bench on river right. “Quiet,” says Colleen. Sound travels far from a river. My paddle blade soundlessly catches water and pulls the boat forward. Only the arc of water drops from my paddle striking the river surface can be heard. Our landing party of ten paddlers scrambles to the rocky shore. Clattering rocks give us away. The herd takes notice. The large male sounds a silent alarm. Blonde and brown fur undulates as sure-footed, skinny legs take the animals up and over a green ridge. Gone.

The Hood River’s surface like a windowpane shows off rainbow-coloured round cobbles speckling the riverbed. Red, gold, pink, black. We paddle at two to three knots. The river travels at a speed of eight or so. The colours speed by underneath the canoe like a kaleidoscope. Occasional wind and waves ruffle the glass.

When the Hood reaches a wide and flat valley, it is braided by gravel islands and lively rapids. The serpentine journey takes us past aromatic lupine meadows and sandy riverbanks. Our five canoes eddy out on river left to set up for lunch. Pussy willows blossom on shrubs, this late in the summer because we are so far north. We line the canoes for a two-night camp. Two curious caribou point their antlers towards us as we pitch tents on rugged tundra. Camp is situated at the top of a series of waterfalls and canyons the Inuit call Kattimannap Qurlua.

The history of this site is invisible. But we know from journals and books that Royal Navy explorers of John Franklin’s 1819-1822 expedition arrived at the base of this waterfall and named it Wilberforce Falls. Franklin and his twenty-two men paddled on wooden skiffs from Fort Enterprise north on the Coppermine River and then east along the northwest passage, mapping the journey. At Baily Bay where the Hood enters Bathurst Inlet, the party camped and waited for supplies that never came. As winter approached, the explorers paddled up the Hood River. They were halted by this waterfall and built sledges from their boats to travel overland back to Fort Enterprise. Poor planning, severe weather, and lack of supplies led to the death of eleven of his men.

There is no sign of these events as I sit on glacially polished pink metamorphic rock covered in slow-growing green and black lichen. The gusting wind from the north and frothy rapids of the river create a melody I hope to remember. The constricted water hurries to a cliff edge with a clear turquoise tongue and tumbles over. Rising mist tells of the waterfall’s great height. This is but one of several waterfalls that has carved a narrow canyon into red stone. Below the first waterfall, the river cascades steeply and travels over further ledges until it reaches the canyon’s terminus ninety metres below and three kilometres downstream.

To portage five canoes and a hundred or so kilos of gear per boat up a ridge, across vegetative meadows and muskeg, and down to the river below the falls takes our group two days of arduous effort. Colin carefully plans the endeavor and encourages efficiency rather than speed. There’s no rush. Enjoy the scenery and experience.

Leslie and I, clearly the expedition’s elders, carry our capacity of some 15 kilos while the strongest among us carry both a canoe barrel and wanigan in one load. They make several round trips. Teams of two to three paddlers haul the four-ply ABS canoes with slings and carabiners across vegetation, sand, and rocks. Boats slither down to the river’s edge. We secure them in willow shrubs.

We portage our personal gear and tents on the second day. The gravel shore at the end of the portage is cloudless and hot. I guess 28 degrees. The best remedy is a plunge into a clear river pool. The guides concoct a lasagna for dinner with sun-melted coconut chocolate bars for dessert. S’mores will have to wait. Nobody has the energy. It was all sapped with the portage. Early to bed.

The next morning a south wind delivers wildfire haze and paints the sun orange. Kerfuffle after breakfast to thread spray skirts, load canoes. Squiggle into dry and semi-dry suits. The waterfall we have left behind marks the point at which the Hood makes a sharp left turn from east to north. The river now aims north to Bathurst Inlet on the Northwest Passage. Once in the water, our five boats ferry to river right. Our skilled guides scout the upcoming right bending rapids with rock pour-overs and holes.

A plan develops. Steer left of the white visible rock, hug near but right of two pour-overs. Avoid wavey holes downstream of them. Though the current seeks to pull you into the holes, steer strongly right towards smooth water. Pat and Leslie successfully thread the rapids. Colleen steers as she and I paddle the course. I pull hard when a large standing wave washes over my head at the crux. We avoid the hazards and reach calm water.

Scott and Zack perilously tilt to the right at the rocky pour-overs and are soon swimming. Pat’s nearby canoe rescues their overturned yellow canoe and rights it while the current pulls it towards the outside left shore. Scott and Zack carefully get back into the swamped canoe. They bail water near a river left eddy and are safe.

Upstream, Whit and Betsy aim for the selected route, but the strong current pulls them too close to the swirly holes. They slide from their right tilt to swim the river. They hold tight to their paddles and swim for the nearby, right shore. Colleen directs me to paddle hard to rescue the canoe. She clips the bow loop with her carabiner to a tow rope. We paddle like mad towards river right, though the current draws us to the middle, where the next set of rapids beckons with open jaws.

Daphnée photographs the entire drama. Colin on shore leaps over sand and stones to grab the tow line so that the red canoe reaches shore. Whit and Betsy have reached the riverbank sand. Their Gortex semi-dry suits have leaked from the neoprene neck gaskets to dribble cold water from chest to toes. “That’s it, I am going to buy a dry suit,” Betsy exclaims as she changes to warm clothes. I have now witnessed two loaded boats swamp on a river expedition. It is a manageable situation; I no longer fear overturning in a canoe should I be the swimmer.

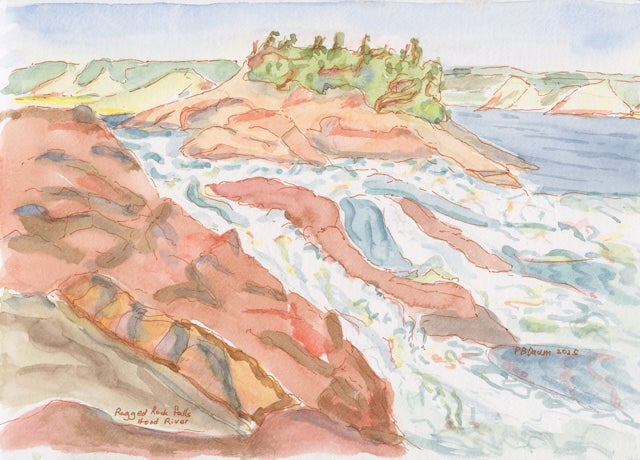

Fire smoke haze follows us downstream. We land in the afternoon at scenic Ragged Falls. Three foaming parallel waterfalls falls separated by red rocks energize my group. We set up camp above the falls but will exit camp below the falls tomorrow. People fish and catch dinner. I paint the scene.

The Hood River gathers in a wide river stretch below the falls. Pat drags our unloaded canoes over smooth rocks right of the falls and plops all into the river below the falls. We can easily descend from camp to load canoes in the morning. Colin checks tomorrow’s weather report. We hope for no headwind as we will paddle north to reach our last campsite. Might rain.

I wake at 4:00 a.m. when Pat clanks the support poles when folding his tent. We plan an early start to beat the wind. We slurp coffee and chew Logan bread with Nutella but no chit chat. Each of us in our own world load boats and launch. Away by 6:00 a.m.

Rain drops bubble on the river. Sights: a couple of caribou, a moose, geese, swans. Wind rises from the north, slight at first. By 9:00 a.m. we arrive at what I call Muskeg Meadow for an obvious reason. Set up camp for two nights. The wind picks up creating whitecaps on the river. All snuggle into tents to sleep off the early start until 4:00 p.m. Tent flys ruffle noisily. Raging wind keeps mosquitoes away when we emerge for dinner.

In breezy sunny weather on our layover day, we take a morning hike north towards a turquoise clear river: I do not know its name. It enters the Hood, which is silty this close to the inlet. Triangular snow shapes in sheltered ravines across from camp form a symmetrical pattern reflected in the river. Wildflowers and shrubs abound. Looks like moose country. After we lunch, we hike to Bathurst Inlet. We find the place where Franklin’s party waited for supplies that never arrived. History speaks loudly here. We find evidence of Inuit camps over the past years. A shard of canvas. Caribou jawbone. Wood fragments. Tent rings. Whet stone.

The channel between us and Victoria Island to the north is the Northwest Passage. Several jump in the Arctic Ocean. Back at home now, I wish I had. On our final day two float planes pick up my group and gear. We doze pensively during the two and one half hour flight to Yellowknife.

At home I close my eyes to feel the peace of Nunavut’s Barren Lands. Memories of the Hood River soothe me. Even when I am not there, I visualize the summer green landscape and imagine the cold wintery months when new snow shapes will form in esker ravines.

For more information on the Hood River trip with Black Feather, or to book, you can click here.

Thanks to Black Feather guides Colin Smith, Colleen Hammond and Pat Eastment for their expertise and excellence on this trip.

Words and art by Hood River 2025 trip participant Tricia Daum. A lyrical and poetry writer, mountain climber and backcountry skier, Tricia Daum is also an avid Black Feather tripper. In 2016, Tricia took her first paddling trip to Banks Island, NWT on the Thomsen River. She has signed up every summer since then to explore northern Canadian rivers and gain tandem canoe whitewater paddling skills. Tricia’s writing and art describe nature, explore quandaries and explain life transitions in poetry, prose poems and essays. Her most recent publication, “Milestones and Reflections”, will be published in 2026.

Photos by Daphnée Rouleau.